Of course, you don’t have to be an exceptionalist to sense there may be something morally dubious about making entertainment out of mass death, or in the complacent assumption that the means of cinema are commensurable with that task. Claude Lanzmann’s magisterial documentary “Shoah” (1985), which famously abjures archival footage of the camps in favor of oral testimony from survivors, perpetrators and bystanders, can be understood in part as a rebuttal to the guileless verisimilitude of “Holocaust.” At nine and a half hours, it was never going to reach as wide an audience as the American TV show, but the way it foregrounds the limits of its representational powers set a standard of artistic integrity against which all subsequent Holocaust films would be measured.

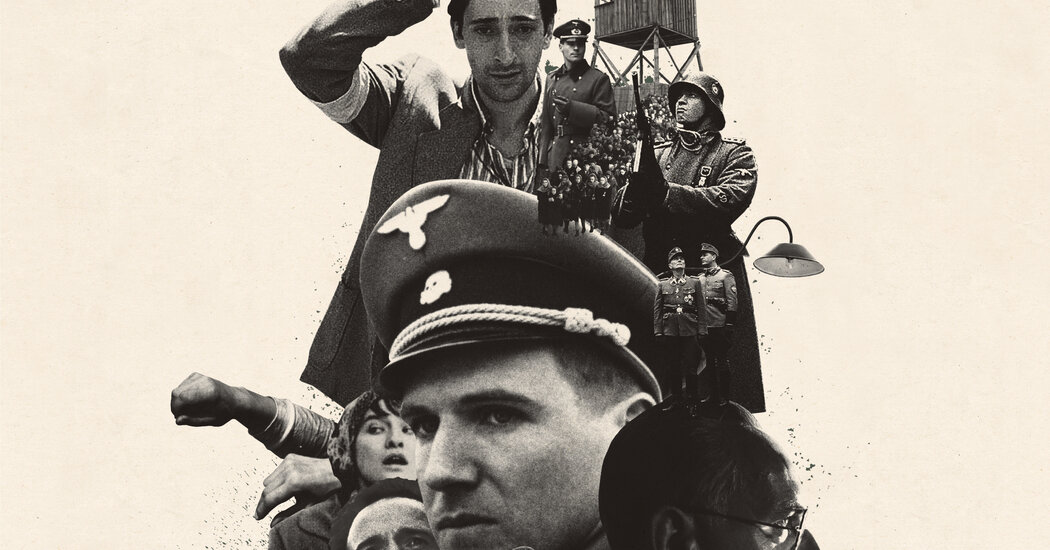

Most of those films, it must be said, have taken their cues more from the NBC series than from Lanzmann’s documentary. “Schindler’s List,” “Life Is Beautiful” (1997) and “The Pianist” (2002), to name just a few, are unalike in many ways, but they all take for granted that the horrors they portray are accessible to cinema. These films have, to their credit, contributed to the de-erasure of the Holocaust, but they have also produced a distorted and simplistic understanding of history. To center the victims, as most films do, makes both moral and commercial sense, but it leaves us in the dark about the perpetrators. In general, the Nazis are drawn as stock villains: They do evil because they are evil.

Some may say that there is wisdom, and decorum, in leaving it at that. In an addendum to his Auschwitz memoir “The Truce” (1963), the writer Primo Levi tries to answer the question “How can the Nazis’ fanatical hatred of the Jews be explained?” but ends up drawing an eloquent blank. “Perhaps one cannot, what is more one must not, understand what happened, because to understand is almost to justify,” he wrote. To understand someone means, in some sense, to identify with him, but for a normal person to identify with Hitler and the Nazi top brass, Levi continues, is impossible. “This dismays us, and at the same time gives us a sense of relief, because perhaps it is desirable that their words (and also, unfortunately, their deeds) cannot be comprehensible to us. They are nonhuman words and deeds, really counterhuman.”

This timeless-sounding passage, it’s worth remembering, was written at a specific historical moment, some 30 years before the belated boom in Holocaust memory got going. To grant understanding to the perpetrators in the 60s, before their victims had been widely recognized as such, may have struck Levi as improper. It’s instructive to compare his proscription with the words of another great chronicler of Auschwitz, the Hungarian novelist Imre Kertesz, who admired him deeply. “I regard as kitsch any representation of the Holocaust that is incapable of understanding or unwilling to understand the organic connection between our own deformed mode of life … and the very possibility of the Holocaust,” Kertesz wrote in an essay from 1998, which condemns “Schindler’s List,” among other works, in terms that echo Rose’s critique. He was thinking, he continued, of “those representations that seek to establish the Holocaust once and for all as something foreign to human nature; that seek to drive the Holocaust out of the realm of human experience.”

Glazer, who steeped himself in Holocaust cinema and history, told me that he is not an exceptionalist. “I don’t like getting involved in a genocide-off,” he said. A few days before we met in Los Angeles, he was in Telluride, where the traces of Native American culture reminded him that Hitler had drawn inspiration from Manifest Destiny, an ideology whose death toll, by conservative estimates, numbers in the tens of millions. When I asked why he decided to tackle the Holocaust, he said it was probably rooted in his family history. Glazer’s grandparents were Eastern European Jews who fled the Russian Empire in the early 20th century. Although his parents weren’t religious, they sent him to a Jewish state school in their North London neighborhood. Bricks were sometimes tossed into the playground by local children bleating slurs.