The party was already going when people entered the theater for Rone and (La)Horde’s “Room With a View” at N.Y.U. Skirball on Saturday night. A heavy beat pounded, and haze hung in the air around a set of huge, crumbling stone steps. In the middle of this hulking structure, the electronic music artist Rone was playing a D.J. set, surrounded by dancers of Ballet National de Marseille. Below, two performers negotiated a private conflict, erotic and aggressive. Euphoria and danger mingled.

Presented as part of Dance Reflections, a bountiful eight-week festival sponsored by Van Cleef and Arpels, “Room With a View” was New York City’s introduction to (La)Horde, the much buzzed-about team at the helm of Ballet National de Marseille. Operating as one entity, its three members — Marine Brutti, Jonathan Debrouwer and Arthur Harel — share an interest in collapsing hierarchies among dance forms and a belief in the continuity of the virtual world and the real world (it’s all one big place). Their past collaborators include Sam Smith and Spike Jonze; they’re the artistic directors of choreography for Madonna’s Celebration Tour.

“Room,” an immersive evening-length work, unsettling but ultimately hopeful, was the stronger of two programs (La)Horde brought to Skirball. In the second, on Wednesday and Thursday, two excerpts from its “Age of Content” shared the stage with dances by the Paris-based choreographer Lasseindra Ninja — celebrated for her work in the European vogueing scene — and the trailblazing American postmodernist Lucinda Childs.

Across the two evenings, some recurring obsessions surfaced: riding the fine line between lust and violence; giving expression to our most primal impulses; tapping into the possibilities of a youthful, rebellious collective spirit. These had a lot more power in “Room,” which, while not overtly narrative, traced a thematic arc, from people treating each other very badly to achieving something like unity through shared resistance.

The program notes for “Room” describe the setting as a marble quarry, but more apocalyptic images came to mind: the ruins of an amphitheater, or a bombed-out building.

Sand spills from the rafters; rubble crashes down with a boom. Together with sudden explosions in Rone’s mostly intoxicating score, some of the work’s images landed as more disturbing than they would have at a less war-torn time in world history.

(La)Horde’s deft use of space pulls our attention in multiple directions. One couple stalks the upper levels of the rocks, trapped in a prolonged, brutal duet, smothering and strangling each other. In the meantime, several dancers down below have removed their clothing — Salomé Poloudenny’s deconstructed street clothes; this is a stylish revolution — and stand with their fists in the air. In a particularly surreal moment, dozens of almost-dead fish fall from the ceiling, flapping. People with brooms come out to sweep them up: an interlude, a reset.

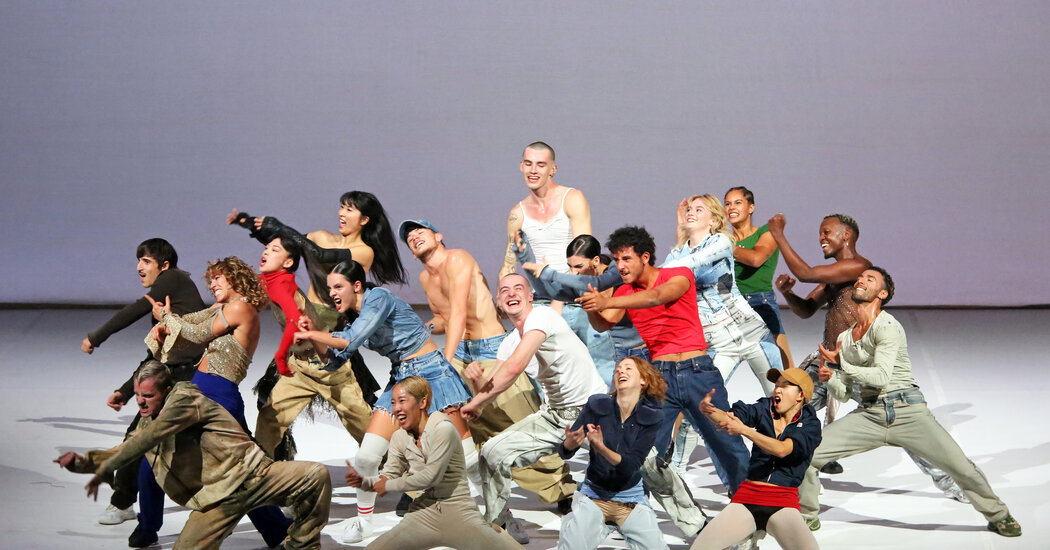

The dancers surround Rone once again, this time on the floor of the stage. Infected by the music, Nathan Gombert breaks away from the group, a fierceness flowing up through his buoyant slashing limbs. The spark he ignited seems to spread. A riotous energy rises, with punches thrown and middle fingers shoved, again and again, at someone out beyond the audience — or, who knows, maybe at us.

In joyfully hurtling, acrobatic partner work, the dancers catapult each other into the air, climb on each other’s shoulders, fall back into each other’s arms. They move closer and closer to unison, eventually finding it in a sublime calm.

Taking in the full, contradictory spectrum of the dancers’ interactions, the collision of fighting and loving, I found myself thinking of fractured political movements, even (especially) those in which people broadly share similar values and aims. The image of an individual lifted up and then devoured by the group appears more than once. No relationship is stable. The harmonious ending resonates only because of the darkness that came before.

(La)Horde’s program with Childs and Ninja was less substantive. Adventurous but aesthetically cluttered, it suffered from its clash of styles, which were more awkward than illuminating side by side. Childs’s orderly minimalism, in “Concerto” and “Tempo Vicino,” bumped up against the bold pulsations of Ninja’s “Mood,” in which dancers strutted in sparkly unitards, cocked their lifted legs like rifles and, in the final section, whipped their high ponytails around to Janet Jackson’s “Throb.”

The two (La)Horde works on the program, “Weather Is Sweet” and “Tik Tok Jazz,” felt one-dimensional compared to “Room,” perhaps because they were excerpted from a longer production. In both, the dancers lean into a brash sexiness more blunt than subversive, and at times enjoyably ridiculous. In contorted configurations and thrusting splits, one person dribbles another’s hips like a basketball. There is a lot of humping the floor.

The ultra-exuberant “Tik Tok Jazz” mixed the clipped vocabulary of TikTok dances with Fosse-esque moves, all delivered with unyielding smiles. Set to Philip Glass’s “Grid,” it couldn’t help but invite comparisons with Childs’s 1979 masterpiece “Dance” — a collaboration with Glass and Sol LeWitt — which kicked off Dance Reflections at New York City Center last week, gorgeously performed by Lyon Opera Ballet.

With its exacting and looping patterns, Childs’s choreography, in itself, embodies the repetition and ongoingness of Glass’s music (“Dance Nos. 1-5”). LeWitt’s black-and-white projections extend and multiply those qualities, creating the mesmerizing effect of a second group of dancers — with a grid as their dance floor — layered over those we see onstage. (Remade for this occasion, with the Lyon dancers instead of the original Childs cast, the projections were no less effective, though less poignant as a comment on the passage of time.)

In very different ways, (La)Horde draws out the same trademarks in Glass’s music, underscoring its relentlessness with a big wink. Pushed far enough, repetition can become sinister. At its best, “Tik Tok Jazz” reveals this deeper level.