Pay attention to the shadows in “Perfect Days.” Pay attention also to the trees, to the ways Hirayama (Koji Yakusho) looks at them. They’re as much a character in the story as he is.

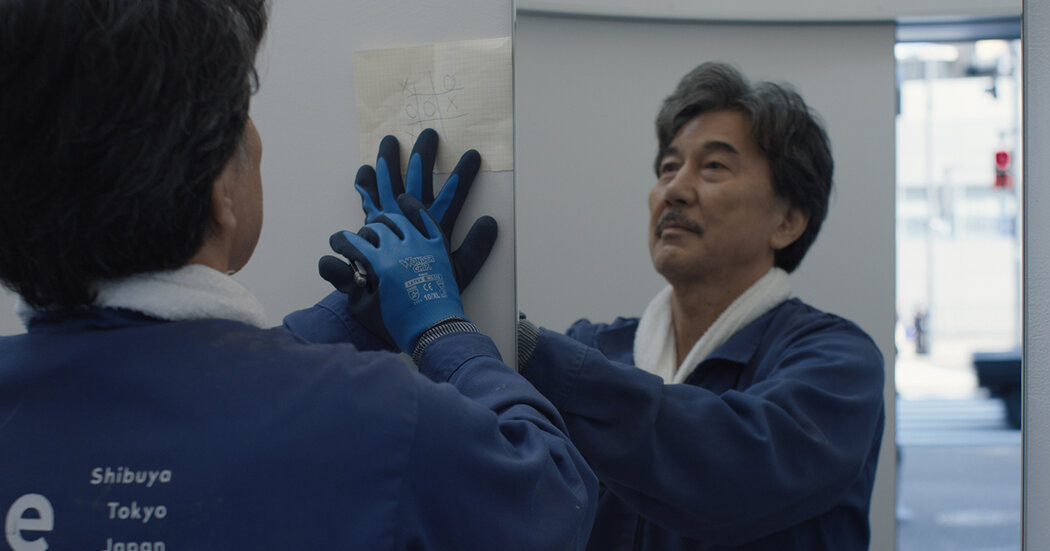

Hirayama cleans Tokyo’s public toilets for a living, rising before dawn to gently water the seedlings he grows in his home and then drive off to begin his shift. On the way to work, he picks a cassette tape — Van Morrison, the Velvet Underground, Nina Simone — and listens while driving down the highway. Tokyo’s Skytree skyscraper looms in the distance.

Hirayama clearly derives enjoyment from performing his work well, but there’s more to his life than labor, and more to this movie than a simplistic celebration of manual toil. He keeps to a simple routine, the kind so carefully constructed you start to wonder if it’s a bulwark against chaos. He exits his apartment and breathes deeply, once, at the same time every morning. He drinks the same coffee, eats the same sandwich, snaps the same photos of the tree canopy. He frequents the same restaurants and bars, public baths and bookstores, places where everyone knows who he is.

Pivotal to his peace is Hirayama’s collection of physical media, a surprising sight in a digital world: In addition to his extensive collection of cassettes, he has shelves of used paperbacks and boxes of tree photographs filed and stashed in his small, neat apartment. They are anchors in time, companions throughout his days, riches rounding out his life. When he brings a book to the bar on the weekend, the proprietor tells him admiringly that he’s such an intellectual. “I wouldn’t say that,” he says.

In fact, Hirayama says very little. (The first time I saw the film, the subtitles were mistakenly turned off, and the audience didn’t even realize for about half an hour.) Instead he is an observer, attending to Tokyo and to the people in it with a tenderness and forbearance that, if you’re not paying attention, you’ll ascribe to a simple nature. It’s only when you watch his expression, at times, that something else flickers, a pain that flashes only briefly. “Perfect Days” chronicles only a couple of weeks — one easy and placid, the other full of disruption — and slowly, exquisitely hints that the structure of Hirayama’s life enables him to exist in the present, representing a choice that may have come after a long trauma. There are clues in his encounters with family members and strangers and, later, in his rattled response to an unexpected sight.

“Perfect Days” — which was Japan’s entry to the Oscars in the international feature category, and landed a nomination — started life when its director, Wim Wenders, was approached about working on a project that would elevate the profile of Tokyo’s pristine public toilets. He proposed a narrative feature, and the film was born.

That may seem an unlikely starting point for a movie like this. But Wenders took the concept and ran with it, painting the story with a wash of nostalgia. Hirayama’s insistently analog life (he asks a young woman what kind of a store “Spotify” is) swings near to feeling gimmicky, but Yakusho sells it with his performance: This is just a guy of a certain age who likes the stuff he likes and feels no need to keep up with whatever the rest of the world is doing. A younger co-worker (Tokio Emoto) pleads with him to turn his tape collection into cash, to get with the times, but Hirayama just isn’t interested. He’s elected to mark the passage of time through his photographs, not through obtaining whatever is new. In some sense, “Perfect Days” is a movie about what we lose when everything becomes digitized.

But there’s something else here. It seems that Wenders’s eye, like Hirayama’s, snagged on the shadows. The canopies of trees are omnipresent in the film, seeping into Hirayama’s dreams at night, which Wenders renders in hazy black and white.

There’s a word in Japanese that transliterates to “komorebi” and refers to a phenomenon for which there is no single word in English: the quality of light as it filters through foliage. Hirayama’s life and mind are full of shadows, despite the sunlight he keeps reaching for. The light of komorebi is not full brightness — it is glistening, ever-changing, full of variation. Hirayama loves this, and he photographs it because the constant capture of what other people miss — the subtle shifts in the canopy every single day — are for him another indication of the trees’ vitality.

Beyond the shadows, trees are a recurring motif in this film. There is the Skytree, which is the world’s tallest tower. In a bookstore, Hirayama buys a book entitled “Tree” by the author Aya Koda — “she deserves more recognition,” the bookseller tells him. And of course, there are the literal trees, always standing near the public toilets that Hirayama cleans. Trees put down roots and grow so slowly and imperceptibly that you can’t really notice. But they’re also markers of time, holding in their rings the evidence of radiation, precipitation, climate change and much more.

I wonder, a little, if Hirayama thinks of himself as related to the trees. When he spots a seedling that won’t grow without proper sunlight, he pulls a small folded pocket made of newsprint out of his wallet, spoons a bit of dirt in, adds the seedling, and brings it home to nurture there. He smiles at the saplings in his home, which he’ll bring outside one day. The trees represent something vital about life, the casting of sun and shadow both vital and inevitable to existence.

The title of “Perfect Days” is a reference to Lou Reed’s song “Perfect Day,” which plays one morning on Hirayama’s tape deck. “You just keep me hanging on,” the chorus repeats. Hirayama’s way of hanging on involves living with the shadows, appreciating the quality of the sunlight and putting down deep, deep roots.

Perfect Days

Rated PG for some beer drinking and an immature co-worker. In Japanese, with subtitles. Running time: 2 hours 3 minutes. In theaters.