The Super Bowl halftime show was at a low point in 2019. Despite an unrivaled television audience, Rihanna turned down the National Football League’s invitation to perform, keeping solidarity with Colin Kaepernick, the exiled quarterback who had repeatedly knelt during the national anthem to protest racial injustice.

The pop band Maroon 5 headlined instead, underwhelming nearly 100 million television viewers. Jon Caramanica, a music critic for The New York Times, called it “an inessential performance” that was “dynamically flat” and “mushy at the edges.”

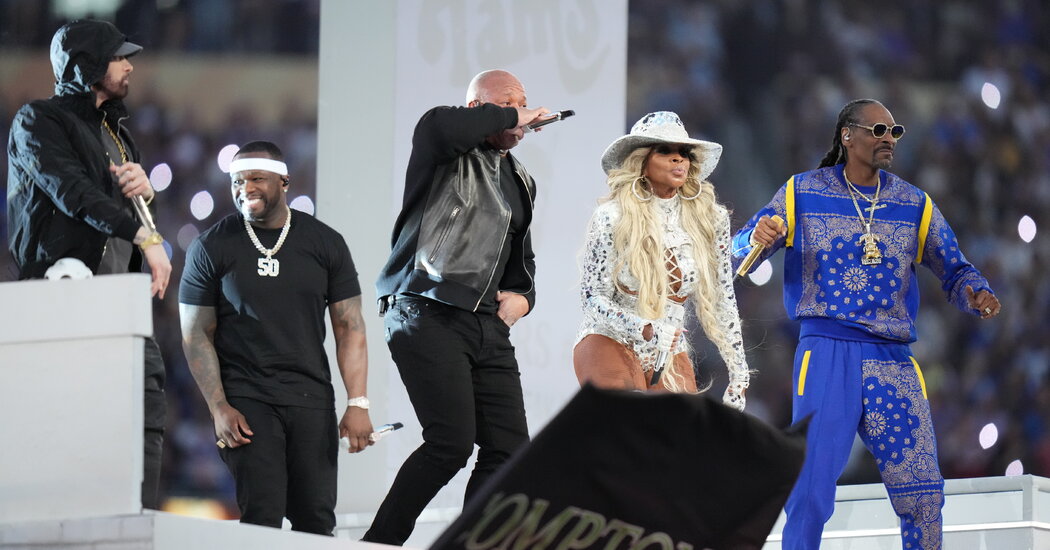

The N.F.L. was quick to respond, courting Roc Nation, the entertainment company founded by the billionaire rapper Jay-Z, in an attempt to strengthen its music and social justice initiatives. Over the past six years, Roc Nation has prioritized hip-hop and R&B, bringing rap to the Super Bowl spectacle for the first time with a celebratory 2022 performance by Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre, Kendrick Lamar, Eminem, Mary J. Blige and 50 Cent. Sunday’s show will feature Lamar and the guest star SZA.

“The N.F.L. needed to do something to bring life to what is supposed to be their signature event, and that was accomplished,” said Jemele Hill, a writer for The Atlantic who is producing an ESPN documentary on Kaepernick with the director Spike Lee.

An overdue emphasis on hip-hop and R&B — Usher and the Weeknd have also headlined under Roc Nation — means that other genres have been sidelined. Country music is ascendant culturally but has rarely been part of the Super Bowl; halftime shows by Coldplay and Lady Gaga feel long in the past.

Nick Holmsten, the former global head of music at Spotify, said he could foresee a backlash if the spotlight did not widen. He questioned the wisdom of employing one long-term partner that might approach the task through a narrow lens. (Apple Music has partnered with the N.F.L. since the 2023 Super Bowl.)

“There are some other candidates that have gained tremendous success in the last year that could have been an option,” Holmsten said. He added, “Even if hip-hop for the last decade has taken the front position, there are still a lot of genres in this country that are massive.”

To this point, Roc Nation has not brought a giant country star like Carrie Underwood or Morgan Wallen, who might appeal to different audiences, to the Super Bowl stage. Shania Twain performed with No Doubt in 2003, a rare presence for country music.

Roc Nation and the N.F.L. declined to comment to The Times. But in a recent interview with The Times-Picayune of New Orleans, the city hosting this year’s game, the chief executive of Roc Nation, Desiree Perez, said she “can’t wait until we get some country music” and noted that Jay-Z’s wife, Beyoncé, on her album “Cowboy Carter” had collaborated with Dolly Parton.

“That’s definitely something we are working on — to make sure that we’re covering all kinds of music,” Perez said.

Roger Goodell, the N.F.L.’s commissioner, said in October that its “mutually positive” partnership with Roc Nation would continue.

Selecting a halftime artist is a complex equation for the N.F.L., which has plans for international expansion and wants to reach as many demographics as possible.

Early Super Bowl shows featured marching bands from historically Black colleges and universities, while the 1990s was filled with superstars like Michael Jackson, Diana Ross and Stevie Wonder. After Justin Timberlake accidentally exposed Janet Jackson’s breast in 2004, the N.F.L. pivoted to classic rock: Paul McCartney, the Rolling Stones, Prince, Tom Petty, Bruce Springsteen.

Now it is the Roc Nation era.

Genres are fluid and the country’s musical tastes shift over time. Last weekend, Lamar won five Grammys for his diss track “Not Like Us,” including for song and record of the year — only the second time a rap song won in those categories.

Todd Boyd, a race and pop culture professor at the University of Southern California, said he felt Roc Nation’s selections had been prudent.

“I think you can be focused and relevant and of the moment and at the same time, potentially include other styles,” Boyd said. “Over time, it’ll automatically work itself out.”

Beyond the debate over performers, some critics say the N.F.L.’s partnership with Roc Nation has not improved the league’s track record on social justice.

Three years ago, a coach sued the N.F.L. for what he calls racially discriminatory hiring practices (it said the claims were “without merit”); the league is also under investigation by attorneys general in New York and California for allegations of workplace discrimination and pay inequities.

In a 2019 news conference, Jay-Z said he wanted to work with the N.F.L. on “actionable items” that went beyond symbolic demonstrations like kneeling. Roc Nation helps with the N.F.L.’s “Inspire Change” initiative, which donates tens of millions to charitable organizations.

“The N.F.L. is more than happy to throw a check at something,” Hill said. “What they wanted to stop is the conversation, the sense of accountability.”

The Super Bowl halftime shows produced by Roc Nation have not been without controversy. Eminem knelt onstage in what was widely interpreted as a nod to Kaepernick. And Jennifer Lopez’s manager said in a Netflix documentary that N.F.L. officials expressed displeasure with portions of her 2020 show over concerns it was making a statement about immigration policies.

Boyd said musicians regularly tackled cultural issues in their work, which clashes with the sports league’s apolitical objective.

“The N.F.L. isn’t trying to sell records,” he said. “They just want people to watch the Super Bowl.”