The Athletic has live coverage of Vikings vs Broncos in Sunday Night Football action.

The retired professor set his laptop aside and reached for the remote. For more than an hour, Chris Pionke had paid little attention to the NFL game on the television in front of him. The teams moved back and forth across the screen and the announcers provided analysis, but Pionke was scrolling mindlessly on his laptop. That changed when he heard the name.

Josh Dobbs.

Pionke, who taught engineering at the University of Tennessee for nearly three decades, perked up and increased the volume. He wondered if the announcers were just mentioning the former Volunteers quarterback, or if Dobbs was actually in the game. He squinted at the screen and spotted a tall, lanky, familiar-looking player wearing the No. 15 in Minnesota Vikings white and purple.

Pionke hollered to his wife who had been sitting over in the kitchen.

“Cindy!” Pionke said. “Josh is in!”

Their Knoxville, Tenn., home livened immediately with football noises. Dobbs barked the pre-snap cadence. Linemen crashed into one another. Announcers yelled, astonished at what they were watching. Pionke listened intently while Dobbs orchestrated a thriller of a victory in relief of rookie Jaren Hall despite having fewer than five days of preparation with his new team.

TOUCHDOWN VIKINGS! TOUCHDOWN VIKINGS!

JOSH DOBBS TAKE OVER THE GAME!

📺: FOX pic.twitter.com/jChQH10AYF

— FOX Sports: NFL (@NFLonFOX) November 5, 2023

The professor cheered excitedly but was not shocked. Those who knew Dobbs well — his former coaches, advisers, mentors, family and friends — felt much the same way.

Their reaction to Dobbs’ public introduction is best summed up by former Pittsburgh Steelers general manager Kevin Colbert, who reiterated the same message five times in a 10-minute phone call:

“If you know Josh, this is not surprising. This is not surprising at all.”

Josh Dobbs showed up in Knoxville wearing a baby-blue suit. Personalized business cards filled his pockets. A detailed schedule laid out his entire day.

Long before he became Tennessee’s starter, months before he even committed to the university, Dobbs took a tour. Alongside his parents, Stephanie and Robert, Dobbs was chaperoned across campus. They visited the football facilities as well as the engineering lecture halls.

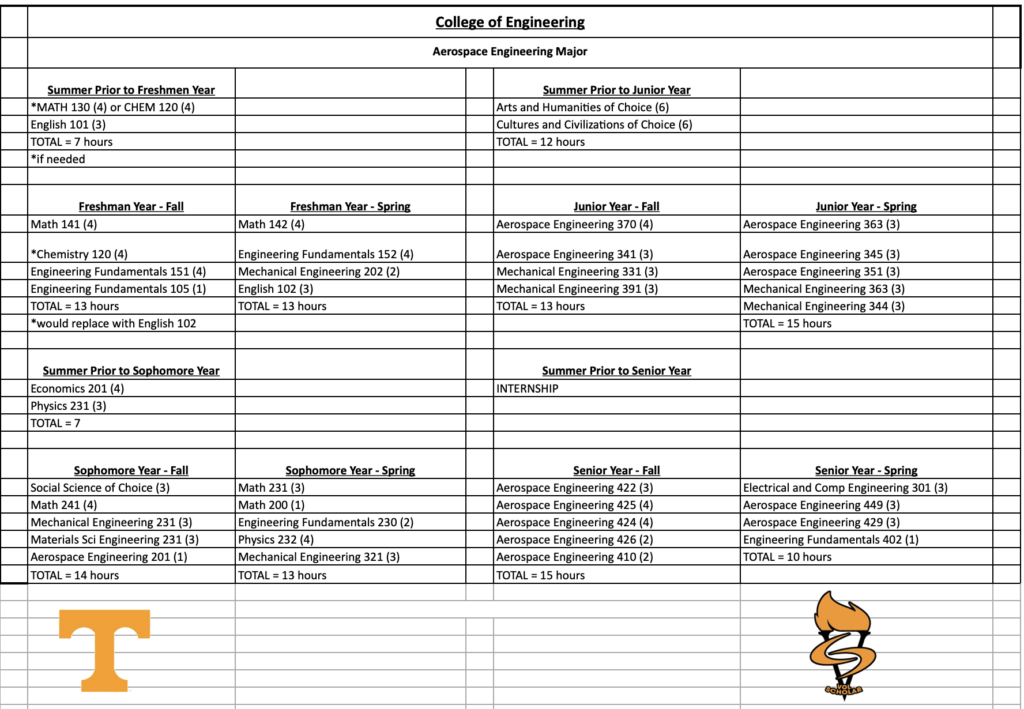

Behind the scenes, the athletic department had orchestrated a meeting with Matthew Mench, then the head of the aerospace engineering department.

Toward the end of their conversation, Mench tossed out a question.

“What math are you currently taking?”

Dobbs deadpanned, “Differential equations.”

Mench’s eyebrow rose as if to say: “How in the hell?”

Differential equations, mind you, typically follows Calculus 1, Calculus 2, Matrix algebra and Calculus 3. A high schooler taking such an advanced class was unheard of.

Why was Dobbs so advanced?

Stephanie, a former UPS executive, and Robert, a longtime banking executive, intentionally exposed Dobbs to an array of subjects as he was growing up in Alpharetta, Ga., outside of Atlanta. They parented with a general creed: The world is yours, and you can do anything you choose.

“To be able to do that,” Stephanie said, “you have to know what’s available.”

Stephanie and Robert sparked the younger Dobbs’ curiosity through yearly trips. They visited different colleges. They explored museums. They wanted their son to absorb it all.

On many of those trips, while sitting idly in bustling airports, Dobbs stood starry-eyed and watched as beautiful machinery disappeared into the sky. Airplanes became a fascination. As a youth, Dobbs asked his parents endless questions about what they were and how they worked. Years later, he would stand at the window and recite the make, model and size of every plane in sight.

As Dobbs reached middle school, his parents pushed him to try numerous activities. They allowed him to play football, basketball and baseball, as opposed to specializing in one. They suggested he try the saxophone. He joined the debate team. Stephanie thought it’d be great for Josh to try the chess club. That is, if he was actually serious about beating her.

“He eventually did,” Stephanie said. “Oh my goodness, I was heartbroken.”

As Dobbs reached high school, math came naturally. Dobbs enjoyed problem-solving and was so proficient that he began taking higher-level math classes at a local community college as an upperclassman. Realizing he could pair his love of flight with his aptitude for math, Dobbs decided to pursue aerospace engineering in college, which Mench described as a subject centered around the physics, materials, structure and propulsion of everything that flies in space.

Advisers tried to talk him out of it, outlining the schedule constraints and workload, but Dobbs would cut them off. Stephanie and Robert backed their son’s vision because they believed in the reward of passionate pursuit. And they knew their son was committed, doubts be damned.

Two days into Dobbs’ first training camp as a freshman at Tennessee, Antone Davis, a UT football staffer, spotted Dobbs sitting on the floor inside the facility.

A playbook was sprawled out on the carpet beside him. Dobbs scanned the pages. Davis thought he’d play a joke on the newbie, so he hollered down the hallway.

“Hey rookie,” he yelled, “you about to learn those plays yet?”

Davis thought Dobbs would squirm. Instead, he looked up and nodded convincingly.

“Yes sir,” Dobbs said. “I know all of the concepts, and I know what they’re trying to do.”

Davis nodded awkwardly and stepped back into his office.

“I was, like, ‘Uhh, OK then.’”

Preparation was never a problem for Dobbs. He awoke at 6:30, attended class from 8-2, practiced and watched film from 2:30-7, then finished his homework in the academic building from 7:30-10. If need be, he’d find extra time for classwork or film study earlier in the morning or later in the evening.

College football fans heard about this the first time Dobbs played a college football game. It was October 2013, and Tennessee’s starting quarterback, Justin Worley, had injured his right thumb. The Vols turned to Dobbs, then a freshman, on the road against Alabama, the best team in the country. On the television broadcast, CBS sideline reporter Tracy Wolfson shared an anecdote that had been relayed to her by a Tennessee staffer.

A few weeks earlier, Tennessee had played Oregon in Eugene. The Vols lost the game and flew home late at night. All of the cabin lights on the flight were dark — except for one. Tucked in the middle of the plane was Dobbs, who sat in the aisle and flipped through thick engineering books.

As Wolfson shared the story, Dr. Christopher Pionke listened and thought: Now I understand how he completed his assignment in honors Engineering Fundamentals 157.

The class, to use Pionke’s own words, was “relentless.” Students attended lectures Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Tuesday and Thursday were reserved for labs, projects and problem sessions. That semester, Dobbs also took four-credit math and chemistry classes.

Backing up Worley helped Dobbs’ prioritization early on even if, away from the cameras, coaches already were making a case for him to play.

During one meeting of the coaching staff, Davis said, a coach interjected: “Guys, who are we going to get to play quarterback?”

Silence enveloped the room for a few seconds, then a defensive coach blurted out, “Josh can do it.”

“He can’t run,” another coach jawed back. “Josh can’t run.”

“Coach!” another defensive staffer said. “We can’t catch him on the scout team. We can’t catch him.”

“I’ll never forget that,” Davis said. “That’s when (head coach) Butch (Jones) decided to give him an opportunity.”

Dobbs played five games his freshman season and entered spring practice in a full-on quarterback competition. Away from the field, he was constructing Olympic medal stands out of foam core and working his connections to secure an internship for the summer.

Late in the spring, Jerry Wheeler, a longtime director of military engines at Pratt & Whitney and a Tennessee alum, received a phone call from a mutual friend of the Dobbs family.

“There’s a member of the football team at Tennessee who would like to intern at Pratt & Whitney during the summer,” the friend said.

“I only know one guy on the football team who is an aerospace engineer major,” Wheeler responded.

“Yeah,” the mutual friend said, “it’s Josh.”

A few months later, while Dobbs could have been enjoying his short break from school, he showed up every day to a control room in West Palm Beach, Fla., to monitor computer display screens that filtered data on an engine mounted in front of them.

Those who knew Dobbs at Tennessee often feel as though they have to offer a clarification.

I swear, they’ll say. He really did all of this!

Sure, in his four years with the Vols, he completed 61.5 percent of his passes for 7,138 yards and 87 touchdowns (53 passing, 32 rushing and two receiving). He led the team to 9-4 marks in his junior and senior seasons, setting several school records along the way. He graduated in 2017 with a perfect 4.0 GPA and won Tennessee’s 2017 Torchbearer Award, the highest honor for an undergraduate student.

But there’s so much more.

One example: the semester Dobbs met one-on-one with a professor each morning because the class was at 3 p.m., the same time as UT’s football practice.

Another example: the time Dobbs left practice immediately to go speak at a Boy Scouts of America banquet three hours down the road in Atlanta. Brian Russell, the team’s academic adviser, drove Dobbs, who sat in the backseat and furiously tapped away at his computer. Upon arrival, he changed into a suit, spoke to the kids and then slept in the car on the three-hour drive back so he could attend class in the morning.

Another example: the time Dobbs held up the Vols’ buses before a road trip because he was spending time with a young girl who had been diagnosed with Alopecia areata, just as he had. Davis had informed Dobbs that spending five minutes with the young girl would suffice. Forty-five minutes later, Dobbs was laughing with the young girl inside Tennessee’s indoor practice facility. She’d worn a wig, nervous about her condition, but Dobbs had made her feel comfortable enough that she took it off just for him. Coaches noticed Dobbs was missing and yelled for him, only to find out later what he’d been up to.

“That was one of the coolest moments,” Davis said. “It was a time where he didn’t have time. And he took time to make time for the little girl.”

In four years, he became a spokesperson for the engineering school. He visited with prospective students, spoke at banquets and met with donors. He mastered time management in a way Russell hadn’t witnessed before (or since) with a student athlete.

“It was like you were dealing with a CEO of a multi-billion-dollar company,” Russell said. “And I mean that seriously. The young man was one of the most special human beings I’ve ever had the opportunity to work with.”

The dynamics of Dobbs’ pre-NFL draft preparations only furthered that feeling. In the spring of 2017, Dobbs split time between Knoxville and Bradenton, Fla., at IMG Academy. A couple of credit hours remained, so he would train at IMG from Friday through Tuesday and attend classes in Knoxville from Wednesday to Friday.

The travel? The mayhem? The different environments? Fulfilling obligations? Working with others? Operating in high-pressure environments?

This is all Josh Dobbs has known.

This past weekend, as Pionke nestled into his recliner to watch Dobbs start another NFL game against the New Orleans Saints, he thought to himself: Finally. The world is getting to see who Josh Dobbs is.

For years, the professor had followed Dobbs’ path and waited for him to get his chance. The Steelers drafted him in 2017 as a developmental option behind Ben Roethlisberger. Colbert, the former GM, said Dobbs wowed the team with his on-field performance. It’s just that the Steelers had a Hall of Famer standing in his way.

Cleveland signed Dobbs to a one-year, $1 million deal in 2022, but cut him late in the season. The Browns asked to bring him back on the practice squad, Stephanie said, but Dobbs felt that joining the Lions’ practice squad would give him the best chance to succeed long term.

GO DEEPER

Josh Dobbs, Browns’ backup QB and a legit rocket scientist, ready if needed

Needing a quarterback late last season, Tennessee identified Dobbs as a player who could learn the Titans offense quickly and “erase the gray when things didn’t play out clean,” said one coach who had a role in the signing. In fact, Dobbs acclimated more quickly than they expected, the coach said, and spoke steadfastly to coaches about tailoring the offense to the players already in the system — not him.

According to agent Mike McCartney, even though Dobbs finished his two Titans starts a mediocre 40-for-68 passing (a 58.8 percent completion rate) for 411 yards, two touchdowns, two interceptions and two lost fumbles, one coach told Dobbs after his final game, “You’re going to be our guy next year.”

A regime change in Tennessee altered those plans, and the Titans ultimately drafted quarterback Will Levis. Only two teams expressed real interest this offseason, according to McCartney: Cleveland and Arizona.

“I remember thinking to myself: ‘Did anybody watch these two Tennessee games?’” McCartney said. “‘Do we not watch the tape? Not one pre-snap penalty in two games with a guy who just arrived nine days before his first start?’ It just didn’t completely make sense that only two teams had interest.”

After reviewing both teams’ infrastructures, Dobbs, now 28, signed with the Browns. During the preseason, though, they traded him to the Cardinals, where finally, after six years of spotty playing time, a game plan was built around his skill set. Eight starts later, following admirable showings against several of the NFL’s best defenses, Dobbs was on the move again.

GO DEEPER

Two Vikings QBs and a whirlwind week: The story behind Josh Dobbs’ arrival in Minnesota

He flew to a new city. He buried himself in a new playbook. He stayed at the facility with Vikings assistant quarterbacks coach Grant Udinski late on Friday afternoon to ensure he could operate the game plan.

In the eyes of Dobbs’ parents, that, really, is the story here. Eschewing the path of least resistance. Exhausting all available resources. Preparing yourself for the opportunity so that when the time comes, the only people who are surprised are the ones who don’t know you at all.

(Top photo: Adam Bettcher / Getty Images)

“The Football 100,” the definitive ranking of the NFL’s best 100 players of all time, is on sale now. Order it here.