One morning in September, a truck disgorged its load of pulverized rock with a resounding bang inside Stillwater Mining’s metallurgical plant north of Yellowstone National Park.

The mined ore contains platinum, palladium and rhodium, three of the earth’s rarest, most expensive metals — and vital components in the millions of catalytic converters that reduce polluting emissions from gasoline-powered vehicles.

At the opposite end of the plant was another batch of metal, not from the mine but from used catalytic converters ground into powder for recycling. The new and the old metals would later be blended under intense heat, then shipped to a refinery.

Recycling catalytic converters costs less than mining the ore. But it carries a risk, as Stillwater discovered after paying more than $170 million for used ones, many of them stolen, according to an indictment handed up this spring on Long Island that implicated the mine. Stillwater was not charged and denied knowing the devices were stolen.

The indictment is an outgrowth of a billion-dollar epidemic of catalytic converter thefts that has not only disabled vehicles but also involved dozens of shootings, truck hijackings and other violence. Replacement devices are often hard to get and can cost $1,000 or more.

Despite public attention on the thefts, little has been known about where the stolen metal goes, who benefits or why stopping the thievery has proved so difficult.

An examination of business records and social media posts, as well as interviews with more than 80 officials on three continents who have ties to the industry, showed that the stolen devices pass through middlemen, smelters and refineries in the United States and overseas. Along the way, their provenance becomes opaque, leaving beneficiaries of the thefts with plausible deniability and little incentive to stop them.

During processing, the metal is blended with legitimate supplies from mines and scrapyards, The New York Times found, before being sold primarily to companies that make catalytic converters for automakers, as well as pharmaceutical companies for cancer and other drugs, military contractors for weapons production, and banks for their precious-metals trading desks, among others.

By then, it is nearly impossible to separate what’s legal from what’s not.

Banks provide short-term financing to process the metals, while other lightly regulated lenders, sometimes called “shadow bankers,” step in when the big banks won’t, Mark Williams, a former Federal Reserve Bank examiner, said in an interview.

Quantifying the thefts is difficult, and estimates vary widely. About 6 percent of the 12 million catalytic converters recycled each year are believed to have been stolen, with the rest coming from scrapyards and other legitimate sources, according to Howard Nusbaum, administrator of the National Salvage Vehicle Reporting Program, a nonprofit group that works closely with law enforcement.

That low percentage is little comfort to the owners of the roughly 600,000 cars whose devices, sometimes known as cats or autocats, were swiped last year. The commercial appetite for the three metals, called platinum group metals or PGMs, has been insatiable.

In an indictment last year involving an auto shop in New Jersey, the shop was accused of selling stolen converters to an unnamed, unindicted co-conspirator, which people with knowledge of the indictment identified as Dowa Metals and Mining America, a Japanese-owned smelter that calls itself “a gateway into the world of PGM metal recycling for North and South America.”

A Dowa spokesman said in a statement that the company “has done nothing wrong and that any allegation to the contrary is false.”

A cottage industry of enablers has grown up around the market. To help thieves assess where and when to strike, the New Jersey auto shop sold access to apps that transmitted up-to-the-minute prices of the metals along with the estimated value of catalytic converters from different vehicles.

“That made it easier for thieves who otherwise would just be slinging dope on a corner to just pull out their phone and be like, ‘Oh, look, there’s a Prius parked across the street — I wonder how much I can get for that?’” said the lead federal prosecutor on a recent indictment.

The thieves have cast a wide net. A Bimbo Bakery delivery truck was hit in New Castle, Del., as were a Mr. Ding-A-Ling Ice Cream truck in Latham, N.Y., and 36 school buses over a single weekend in one Connecticut community. Amy Foote, an opera singer in the San Francisco Bay Area, said 11 of the devices had been stolen from her Toyota Prius. She called the car “a vending machine for catalytic converters.”

Authorities have dismantled several nationwide criminal rings trafficking in the devices and many states have introduced new laws. But the thefts continue, even as prices for the metal have dipped.

The subject arose repeatedly at a recent conference of the International Precious Metals Institute in Orlando. Lee Hockey, a consultant formerly with Johnson Matthey, a specialty chemical company, addressed culpability head on.

“Most people in this room will see petty thefts and say, ‘Oh, we’re not involved in that,’” Mr. Hockey said. “But everybody is. If you’re a refiner, even if you are dealing with a smelter, you are getting the metal, so you are liable. If you are an insurance company and you are insuring people on the site, you are liable. If you are doing an analysis of the sample, you are liable.” He added, “You are along the supply chain, and you are involved.”

Greg Roset, a former manager of Stillwater’s recycling program in Montana, answered unequivocally when asked in an interview if he ever worried about stolen metal entering the supply.

“Yes,” he said, “always.”

How It All Began

The frenzy over grimy metal casings underneath cars traces back to a barren strip of rocky land in South Africa’s so-called Platinum Belt.

For more than 100 years, gold reigned supreme in that country but by 2005, a confluence of events, set off partly by the auto industry, had deposed gold in favor of PGMs.

In the 1960s, as concern in the United States mounted over worsening air quality, environmentalists pointed to millions of cars belching toxic fumes from their tailpipes. Smog blanketed many major American cities.

In response, Congress passed the Clean Air Act of 1970, which included a provision requiring all vehicles manufactured after 1975 to sharply reduce pollutants. Automakers objected, saying it was not technologically possible.

But researchers at Engelhard Corporation, a metals processing company in New Jersey, found that platinum group metals could catalyze, or convert, unburned hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide and nitrogen oxides into less harmful forms. To be effective, the catalysts had to be durable, have a high melting point and resist corrosion.

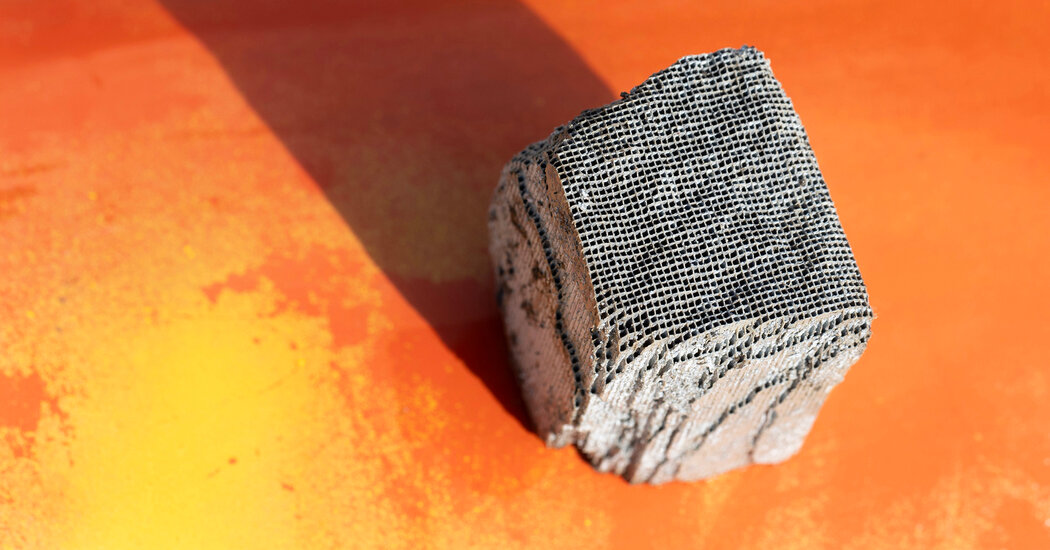

Engelhard coated a ceramic honeycomb screen with a thin layer of PGMs and placed it inside a metal container through which the engine exhaust passed.

“It stands as one of the greatest technological interventions to protect the environment in history,” said Ken Cook, president of the Environmental Working Group, an advocacy organization.

As an added benefit, the precious metals are recyclable. A single converter contains only a small amount, but with millions of cars on the road, all that rare metal being recycled only from scrapyards struck some people as a lost opportunity.

And so, a thriving underground network of thieves took root.

Follow the Metals

On a cold day in March 2022, DG Auto issued an urgent phone alert: “Palladium breaks $2,900, reaching its highest price since June 2021.” Noting that prices on average had risen 15 percent the week before, the company suggested downloading its app “to make sure you’re getting the best price for your converter.”

DG Auto also showed an interest in international affairs. “Metal prices are moving as China’s lockdowns ease up,” the company texted customers. “Shanghai is slowly reopening and Beijing lockdown is not likely.”

In an industrial park in Freehold, N.J., less than a half-mile from a state vehicle inspection station, DG Auto became one of the nation’s biggest buyers and sellers of stolen catalytic converters, according to the authorities.

Customers who paid $29 a month for its “platinum package” could submit pictures of the devices for estimates, along with other services.

In the indictment last year, a federal grand jury accused DG Auto of selling stolen converters to the unindicted co-conspirator, identified to The Times as Dowa Metals and Mining America.

“Our strength is in our ability to collect spent catalysts by ourselves, which enables us to obtain market information with relative ease,” Akira Sekiguchi, Dowa’s president, told investors last year.

At the time, Dowa was part owner of a metal-testing company, Nippon PGM America, along with Tanaka and Toyota Tsusho America, a unit of Toyota Motors, according to Nippon’s website. Neither Tanaka nor Toyota were mentioned in the indictment or accused of wrongdoing. In a statement, Tanaka said there was “no direct contractual relationship” between it and Dowa.

Last month, three people pleaded guilty to their role in the nationwide conspiracy to ship $600 million of stolen catalytic converters from California to DG Auto. Five co-defendants have pleaded not guilty.

Best practices for the industry emphasize buying autocats from known, reputable suppliers that can trace the devices’ origins. Even so, stolen converters enter the supply chain.

Experienced auto theft investigators prefer to focus on companies buying the metals. Joseph Boche, a former director of the International Association of Auto Theft Investigators, said the thefts would mostly stop if basic rules were followed nationally: identify the person selling the device and the vehicle from which it was removed, require traceable payment, prohibit cash transactions, and maintain sales records.

But support has been uneven, he said. In the spring of 2021, a group of smelters and refiners contacted him to combat the thefts. “But they didn’t like any of my suggestions,” he said, “and stopped inviting me to any of their meetings.”

The Montana Mine

Montana is one of the few places in the world where the metals used in catalytic converters are mined. Extracting the deposits is costly, requiring twin tunnels dug 3.5 miles underground.

To augment its supply, Stillwater began buying catalytic converters for recycling, a cheaper method and less harmful to the environment.

“Blending materials from two different sources gives us a competitive advantage over other recycling facilities,” the company website states. “Our Montana mines contain quantities of nickel and copper which facilitate extraction of the PGMs from the recycled material.”

Over the past decade, the Stillwater plant processed more PGMs from the used devices than from its Montana mines, Heather McDowell, a company official, said during a recent tour. To keep the pipeline of recycled devices flowing, she said, Stillwater relies on 28 suppliers.

All of the PGMs are sent for final refining to Johnson Matthey for use in, among other things, “the vital compounds — known as active pharmaceutical ingredients,” it said in its 2021 annual report.

Pfizer, for example, uses platinum for chemotherapy treatments. “Pfizer has a diverse supply chain network and has not relied on a sole supplier,” the company said in an email response to questions from The Times about Stillwater. The company declined to say whether Stillwater is one of those suppliers.

When Stillwater needed to prime the pump, it advanced cash to “third-party brokers and suppliers to support the purchase and collection of spent autocatalytic materials,” the company wrote in a regulatory filing.

In the past, those payments totaled in the tens of millions of dollars, court records show.

For other companies, lenders step in with short-term financing, according to industry documents and interviews with five precious-metals experts. Some loans are used to buy catalytic converters to “keep the wheels spinning” on the recycling business, one precious-metals executive said.

JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs provide short-term financing for metal processors, according to Ruth Crowell, chief executive of the London Bullion Market Association, a trade group that sets standards for the precious-metals industry. JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs did not respond to requests for comment; a spokesman for Morgan Stanley declined to discuss lending practices.

In an 81-count indictment in Nassau County, N.Y., this spring, prosecutors said Stillwater had paid an accused criminal operation more than $170 million for catalytic converters, many of them stolen. The indictment charged two brothers, Alan and Andrew Pawelsky, with orchestrating the thefts and using the proceeds of their Stillwater sales to buy more stolen devices.

The brothers deny the accusations, and court records show that Stillwater cut ties with them last December when their alleged criminal activity became public. Stillwater denied knowing the devices were stolen and said it was now setting the industry standard by requiring vendors to “undergo a robust diligence review.”

In court papers, Alan Pawelsky acknowledged that his company, Ace Auto Recycling, had a “lucrative contract” with Stillwater, which allowed it to “become a broker in the industry for others that had large volumes of cats.”

In a statement, Gerald M. Cohen, a lawyer for Mr. Pawelsky, described him as “a hard-working American success story who went out of his way to comply with the law, avoided buying stolen materials and was always willing to assist law enforcement.”

Stillwater has also been a business partner with Global Refining Group, a family of companies that includes Alpha Recycling in the Bronx and Alpha Shredding Group in New Jersey, according to Global’s website. Both firms were implicated in other investigations related to the purchase of stolen material, according to court records.

Justin Mercer, a lawyer representing Global Refining, said in an interview that his client sourced material only from responsible suppliers and in recent years had “doubled down on compliance.” But, he acknowledged, such steps only “reduce the likelihood” of taking in stolen goods.

The former Stillwater recycling manager, Mr. Roset, said it would be “naïve to believe that nothing ever sneaks into the system,” because the network is so large. For companies like Stillwater, he said, “There’s no way to determine the origin of the metal. But the collectors — it’s on them to have integrity.”

Shootings and Stabbings

Darren Almendarez, a sheriff’s deputy in Harris County, Texas, had recently begun investigating catalytic converter thefts in the Houston area in March 2022 when he spotted three men attempting to steal the one from his own Toyota Tundra.

Though off duty, he confronted the men in a grocery parking lot. A gun battle ensued, and Mr. Almendarez was killed.

The thefts have brought about a wave of violence that speaks to the value of the metals inside the devices. Since 2021, there have been almost four dozen shootouts, in addition to stabbings and countless fistfights.

Victims of the thefts cut across social and economic lines.

In the summer of 2021, thieves snatched seven from Silver Key Senior Services, which provides transportation for elderly and developmentally disabled people in Colorado Springs, Colo. In May, more devices were stolen from their vehicles and from two partner organizations. Replacements cost roughly $40,000.

Ms. Foote, the Bay Area opera singer who had 11 stolen from her Prius, said that for a while it happened at least once a month.

She had a protective plate installed, but thieves cut around it. Other solutions suggested by the police included getting the device engraved, which seemed pointless to her.

“The people selling the cats don’t care,” Ms. Foote said.

The Prius is a popular target because of its high PGM content. With so many Prius owners seeking replacements, wait times in some parts of the country have stretched up to a year.

All told, about 24 percent of all PGMs come through the recycling of catalytic converters, according to Braeton J. Smith, an economist at the Department of Energy.

An International Problem

Some countries are experiencing a different kind of criminality: the hijacking of entire truckloads of new catalytic converters. In February, robbers nabbed a truck in southern Germany with a load worth $1.5 million.

South Africa, in particular, has experienced escalating violence, Julian Kohle, government affairs manager with the International Platinum Group Metals Association, wrote in a recent article for the group.

He cited an incident in which gangs had shot a guard and taken about $2.5 million in precious metals from a truck in Port Elizabeth. A South African business group blamed international organized crime syndicates that jam security and tracking devices, he wrote.

Experts say the first step to stopping precious-metal thefts is to demonstrate the true scale of the crime.

American news reports often cite claims data from the National Insurance Crime Bureau, which recorded 64,000 catalytic converter thefts last year. But that number does not include thefts reported to the police, devices stolen from uninsured vehicles, or even all insurance claims, according to the National Salvage Vehicle Reporting Program.

“Lots of people don’t file claims because there’s a $500 deductible,” said Mr. Nusbaum, the group’s administrator. He added that many insurers don’t have a separate reporting category for this crime. His organization estimates that there are more than 10 times as many thefts annually as the insurance group’s tally.

The insurance bureau’s president, David Glawe, acknowledged in a statement that his most recent data was “just a snapshot of an underreported crime.”

Tate Hewitt contributed reporting, and Julie Tate contributed research. Reporting was supported in part by the Global Reporting Centre at the University of British Columbia.

Audio produced by Adrienne Hurst.