“We live in terror,” whispers Layla over the phone so nobody can hear. She fled Sudan with her husband and six children early last year in search of safety and is now in Libya.

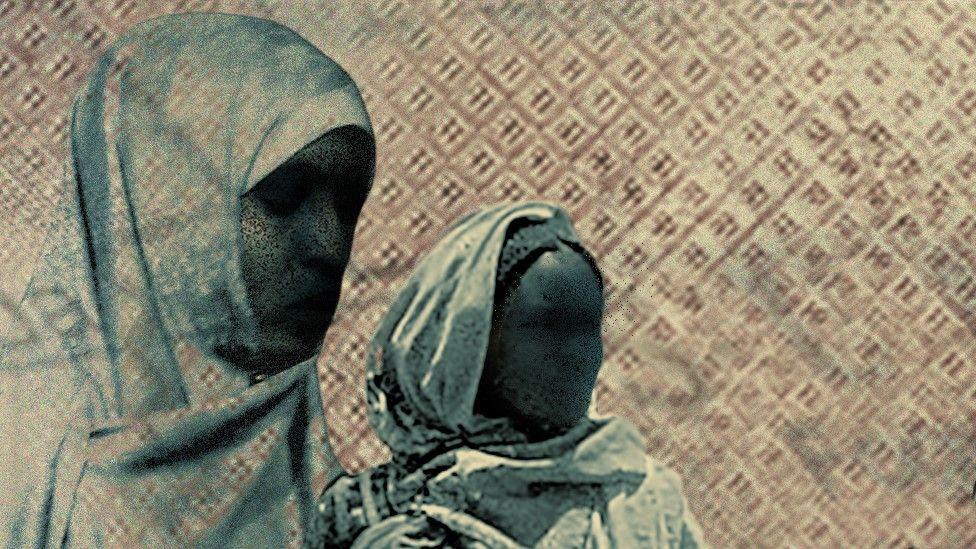

Like all the Sudanese women who the BBC spoke to about their experiences of being trafficked to Libya, her name has been changed to protect her identity.

Warning: This story contains details some may find distressing.

In a trembling voice she explains how her home in Omdurman had been raided during Sudan’s violent civil war, which erupted in 2023.

The family went to Egypt first before paying traffickers $350 (£338) to take them to Libya, where they had been told life would be better and they would be able to find jobs in cleaning and hospitality.

But as soon as they crossed the border, Layla says the traffickers held them hostage, beat them and demanded more money.

“My son needed medical attention after he was hit repeatedly in the face,” she tells the BBC.

The traffickers released them after three days, without saying why. Layla thought her new life in Libya was starting to get better after the family managed to travel west and she rented a room and started working.

But one day her husband left to look for work and never returned. Then her 19-year-old daughter was raped by a man known to the family through Layla’s job.

“He told my daughter he would rape her younger sister if she spoke about what he did to her,” Layla says.

She speaks in hushed tones fearing the family will be evicted if their landlady hears about the threats.

Layla says they are now trapped in Libya: they have no money left to pay traffickers to leave and cannot return to war-torn Sudan.

“We have barely any food,” she says, adding that her children are not in school. “My son is afraid to leave the house as other children often beat him and insult him for being black. I feel like I’m going to lose my mind.”

Many Sudanese refugees fled to Egypt when conflict erupted in April 2023 before then crossing into Libya [Getty Images]

Millions have fled Sudan since the war between the army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) erupted in 2023. The two sides had jointly staged a coup in 2021, but a power struggle between their commanders plunged the country into civil war.

More than 12 million people have been forced from their homes, while famine has spread to five areas, with 24.6 million people – about half the population – in urgent need of food aid, experts say.

The UN refugee agency says more than 210,000 Sudanese refugees are now in Libya.

The BBC has spoken to five Sudanese families who initially went to Egypt, where they said they experienced racism and violence, before moving to Libya, believing it would be safer with better job opportunities. We contacted them through a researcher in migration and asylum seeker issues in Libya.

Salma tells the BBC she was already living in Cairo, in Egypt, with her husband and three children when the Sudanese civil war broke out, but as huge numbers of refugees entered the country, conditions for migrants there worsened.

They decided to move to Libya, but what was awaiting them there was a “living hell”, Salma says.

She describes how, as soon as they crossed the border, they were placed in a warehouse run by traffickers. The men wanted money that had been paid in advance to traffickers on the Egyptian side of the border, but it never arrived.

Her family spent nearly two months in the warehouse. At one point, Salma was separated from her husband and taken to a room for women and children. Here, she says she and her two eldest children were subjected to various forms of brutality because they wanted the money.

“Their whips left marks on our bodies. They would beat my daughter and put my son’s hands in a lit oven while I was watching.

“Sometimes I wished we would all die together. I could think of no other way out.”

Salma says her son and daughter were traumatised by the experience and have suffered from incontinence since. She then lowers her voice.

“They would take me to a separate room, the ‘rape room’ with different men each time,” she says. “I bear the child of one of them.”

Eventually, she raised some money through a friend in Egypt and the traffickers released the family.

She says a doctor then told her it was too late for an abortion, and when her husband found out she was pregnant he abandoned her and the children, leaving them to sleep rough, eating leftovers from rubbish bins and begging in the street.

They found refuge on a remote farm in north-western Libya for a while, spending whole days with little to no food. They quenched their thirst by drinking contaminated water from a nearby well.

“It breaks my heart to hear my [older] son saying he is literally dying from hunger,” Salma says over the phone, as the cries of her baby grow louder in the background.

“He is so hungry,” she says, “but I have nothing, not even enough milk in my breasts to feed him.”

The war between the army and the RSF has caused widespread destruction across Sudan [Getty Images]

Jamila, a Sudanese woman in her mid-40s, also believed reports within the Sudanese community that a better life awaited them in Libya.

She fled previous unrest in Sudan’s western region of Darfur in 2014 and spent years in Egypt before moving to Libya in late 2023. She says her daughters have been raped repeatedly since then – they were 19 and 20 when it first happened.

“I sent them for a cleaning job while I was ill; they came back at night covered with dirt and blood – four men raped them until one of them fainted,” she tells the BBC.

Jamila says she was also raped and held captive for weeks by a man, much younger than her, who had offered her a job cleaning his house.

“He used to call me a ‘disgusting black’. He raped me and said, ‘This is what women were made for,'” she recalls.

“Even kids here are mean to us, they treat us as beasts and sorcerers, they insult us for being black and African, are they not Africans themselves?” Jamila says.

When her daughters were raped the first time, Jamila took them to hospital and reported it to police. But when the police officer realised they were refugees, Jamila says he withdrew the report and warned her that she would be jailed if the complaint was officially filed. This was in the west of Libya.

Libya is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention or the 1967 protocol relating to the Status of Refugees – and considers refugees and asylum-seekers “illegal migrants”.

The country is divided into two, with each part run by a different government, but the situation is easier for migrants in the east as they can file official complaints without being detained, and access healthcare more easily, according to human rights group Libya Crimes Watch.

While sexual violence is common within unofficial facilities run by traffickers, there is also evidence that abuse is happening in official detention centres in Libya, especially in the west.

The UN refugee agency says more than 210,000 Sudanese refugees are now in Libya [Getty Images]

Hanaa, a Sudanese woman who works gathering plastic bottles from bins to feed her children, says she was abducted in western Libya and taken to a forest and raped at gunpoint by a group of men.

The next day her attackers took her to a facility run by the state-funded Stability Support Authority (SSA). Nobody told Hanaa why she had been detained.

“Young men and boys were beaten and forced to completely remove their clothes while I was watching,” Hanaa tells the BBC.

“I was there for days. I slept on the bare floor, resting my head on my plastic slippers. They would let me go to the toilet after hours of begging. I was repeatedly beaten on the head.”

There have been numerous previous reports of migrants from other African countries being abused in Libya. The country is a key stepping stone on the way to Europe, although none of the women the BBC spoke to planned to travel there.

In 2022, Amnesty International accused the SSA of “unlawful killings, arbitrary detentions, interception and subsequent arbitrary detention of migrants and refugees, torture, forced labour, and other shocking human rights violations and crimes under international law”.

The report states that Ministry of Interior officials in the capital, Tripoli, told Amnesty that the ministry had no oversight over the SSA since it answers to the prime minister, Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh, whose office did not respond to our request for comment.

Libya Crimes Watch has told the BBC that systemic sexual abuse of migrants takes place in official migrant detention centres, including the notorious Abu Salim prison in Tripoli.

In a 2023 report, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) said there was an “increasing number of reports of sexual and physical violence, including systematic strip and intimate body searches and rape” at Abu Salim.

The interior affairs minister and the Department for Combating Illegal Migration in Tripoli did not respond to our request for comment.

Salma has now left the farm moved into a new room with another family nearby, but she and her family still face the threat of eviction and abuse.

She says she cannot go back home because of what happened to her.

“I bring shame on the family, they would say. I’m not sure they would even welcome my dead body,” she says. “If only I had known what was awaiting me here.”

Map

You may also be interested in:

[Getty Images/BBC]

Go to BBCAfrica.com for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica