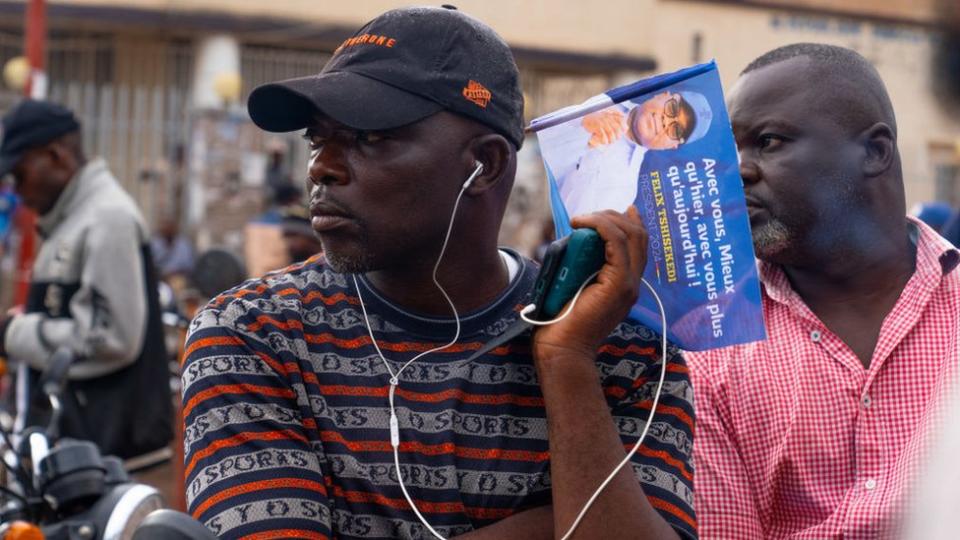

Félix Tshisekedi is being sworn in for a second term as Democratic Republic of Congo president following a chaotic, disputed election.

He has another five years to improve the fortunes of a nation where more than 70% of people live in extreme poverty and decades of conflict have plagued the lives of millions.

So can Mr Tshisekedi bring that long yearned-for peace to DR Congo? Or have heightened violence and the president’s campaign pledge to go to war with neighbouring Rwanda ruined any chances of that?

During both of his presidential campaigns, Mr Tshisekedi has vowed to tackle the unrest in eastern DR Congo.

Dozens of armed groups – including the notorious M23 – battle for control of land, and the region’s abundant minerals, which include gold, diamonds and cobalt, essential for batteries in mobile phones and electric cars.

Last year, conflict between the groups flared after a months-long lull and the number of people forced to flee their homes reached a record 6.9 million, according to the UN.

To bring all this to an end, Mr Tshisekedi needs to reshift his focus from “short-term” military initiatives to lasting solutions, Richard Moncrieff, Great Lakes Project director at the International Crisis Group (ICG), tells the BBC.

President Tshisekedi and other African leaders had started negotiations – known as the Nairobi and Luanda processes – in an attempt to ease DR Congo’s insecurity through military and political strategies. However, these talks appear to have stalled.

The Congolese president hasn’t paid keen attention to any of the peace processes, Mr Moncrieff argues, adding: “He needs to build for the long term in terms of reforming his security sector… and not place so much trust in very, very unreliable short-term solutions.”

Military initiatives taken by the president in his first term include declaring a state of siege in the provinces of Ituri and North Kivu, in 2021.

He attempted to restore order by appointing military leaders to replace the civil administration in the areas.

Additionally, the president pushed for a recruitment drive that led to thousands of young people joining the army, while launching a disarmament operation aimed at reintegrating members of armed groups into civilian life.

Critics point out that these initiatives have failed to reduce fighting in the east, even though Mr Tshisekedi insists they have borne fruit.

He told MPs in November there had been a “reduction of cross-border mining and customs fraud which fuels conflicts”, as well as an improvement in intercommunity tensions and “the reestablishment of state authority”.

The president has also said getting rid of an East African force set up to curb DR Congo’s conflict, and replacing it with a southern African one, will help to reduce insecurity.

In October 2023, DR Congo’s government said it would not extend the East Africa Community (EAC) Regional Force’s mandate after months of Kinshasa complaining about the troops’ ineffectiveness.

Last month, the Congolese foreign minister said troops from the southern African bloc SADC had been given the mandate “to support the Congolese army in fighting and eradicating the M23 and other armed groups that continue to disrupt peace and security”.

It remains to be seen whether SADC can contain DR Congo’s multiplicity of militias, which the forces before them, including the UN peacekeepers who have been in the country since 1999, have failed to do.

The UN mission, known as Monusco, is set to complete its withdrawal from DR Congo at the end of this year – after President Tshisekedi’s government deemed them to be ineffective.

Alongside cutting ties with forces from the UN and EAC, President Tshisekedi has threatened to go to war with Rwanda.

“If you re-elect me and Rwanda persists… I will request parliament and Congress to authorise a declaration of war. We will march on Kigali,” he said in December, in his final campaign rally.

He accuses Rwanda of supporting the M23 rebel group. A UN group of experts made a similar observation in a 2023 report, with the US backing its findings.

Rwanda has always denied the claim and accuses its neighbour of backing Hutu rebels who stage attacks in Rwanda.

President Tshisekedi has threatened to attack Rwanda a number of times before, but has not yet followed through. Many believe these pledges were simply a bid for the nationalist vote.

Following Mr Tshisekedi’s most recent pledge, Rwandan President Paul Kagame said anyone who wished for his country’s destruction “will experience it instead”.

Mr Kagame’s words indicate Rwanda would respond with force to any “march on Kigali” and President Tshisekedi would not only have failed to bring peace to DR Congo, but would have drawn more violence to his own country.

And Rwanda’s army is one of the most respected in Africa, while DR Congo’s is notorious for corruption and ill-discipline.

But having made the threat, Mr Tshisekedi “will find it difficult to row back from the bellicose rhetoric that he used in the election campaign”, Mr Moncrieff said.

In DR Congo, peace does not only mean the defeat of M23 and its fellow armed groups. The Congolese people will also expect their president to facilitate dialogue which addresses disputes between the nation’s numerous ethnic groups, which past leaders have not successfully tackled.

He must also deal with the political row caused by the disputed elections.

Ahead of the inauguration, three opposition leaders and presidential candidates who lost out to Mr Tshisekedi called for protests during the ceremony.