The proliferation of documentaries on streaming services makes it difficult to choose what to watch. Each month, we’ll choose three nonfiction films — classics, overlooked recent docs and more — that will reward your time.

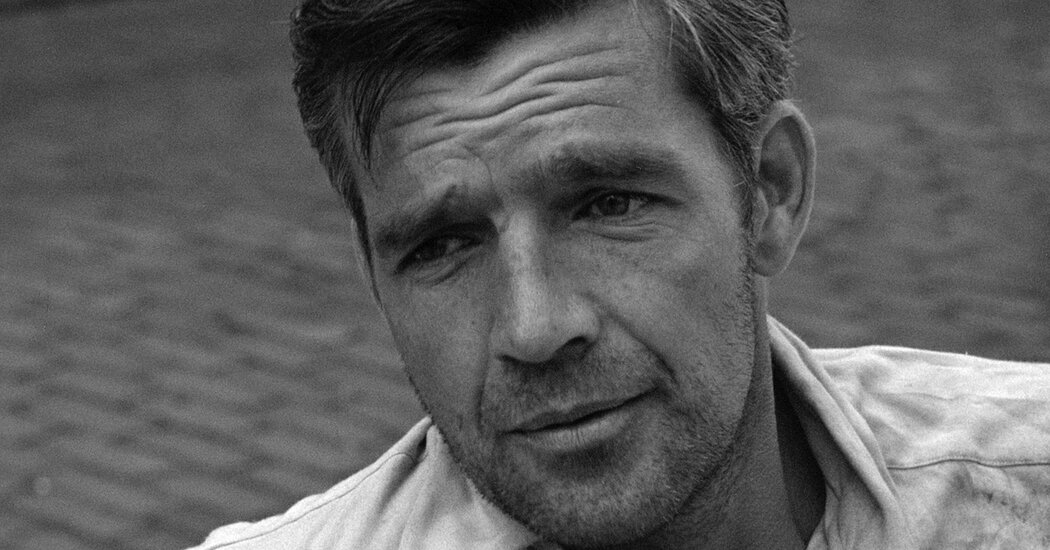

‘On the Bowery’ (1957)

Stream it on the Criterion Channel, Kanopy and Ovid. Rent it on Amazon and Milestone.

“On the Bowery,” the director Lionel Rogosin’s classic portrait of life on skid row, is not only a time capsule of a bygone New York, but also of a bygone form of documentary filmmaking. To be fair, Rogosin (1924-2000), in a 1987 interview, said that he disliked the word “documentary,” which he found “deadening.” But the movie, like Robert J. Flaherty’s “Nanook of the North” and “Man of Aran,” also clearly involves a degree of staging. Soon after, in films like Robert Drew’s “Primary” (1960) and the work of the brothers Albert and David Maysles, lightweight, portable sound equipment would make so-called “direct cinema” possible. “On the Bowery” doesn’t have that offhandedness. Rogosin, who spent six months observing life on the Bowery before starting to shoot, recruited real-life denizens of the area to essentially play themselves — “men of the Bowery,” as the opening credits call them, although there are a few women around as well.

The film opens with a shot of the Third Avenue subway (which hadn’t yet been dismantled) and turns into a sort of reverse city symphony; instead of the monumentality of buildings or crowds, Rogosin dares to show men sleeping on sidewalks or on park benches. This portion of the film is silent except for a musical score. But the camera soon enters a bar and begins to hear from the men. The heart of “On the Bowery” is the friendship that forms between two alcoholics, Gorman Hendricks, a former doctor, and Ray Salyer, a railroad worker who eventually commits to at least the aspiration of going sober, something about which Gorman harbors few illusions. The two men bond over selling some of Ray’s clothes to get money for more drinks.

Rogosin said he worked from an outline as opposed to a script. Some of the dialogue is frankly expository, seemingly designed to educate viewers. “What’s the story here? What’s the setup?” Ray asks another man while they wait in line to be admitted to a mission, and the man responds with details on how getting a bed works and on how long residents are allowed to stay. Later, there is a moment in which Ray is beaten up and then robbed on camera, in the sort of spontaneous incident that even a devoted direct-cinema practitioner would have been unlikely to capture; the number of shots is a tipoff that this is a re-creation. But what is shown is nevertheless Ray’s reality. And whatever limitations it may have had, “On the Bowery” is still an unvarnished look at poverty and alcoholism in the 1950s.

‘Beyond Utopia’ (2023)

Stream it on Hulu. Rent it on Amazon, Apple TV, Fandango at Home and Google Play.

There is access, and then there is what we see in Madeleine Gavin’s documentary about defectors from North Korea. The film is a portrait of the labyrinthine and extremely dangerous process of escaping from Kim Jong-un’s regime. Anyone who manages to make it across the Yalu River, which forms North Korea’s border with China, must then navigate a course through multiple countries to ultimately reach South Korea. Gavin’s documentary profiles people like Seungeun Kim, a pastor who has taken it as his mission to secure safe passage for North Koreans, and Soyeon Lee, a past defector who hopes that her son will join her in the south but hasn’t seen him in 10 years. Given that he has spent those 10 years ingesting propaganda in North Korea, it is difficult to know how he feels.

But the biggest coup in “Beyond Utopia” is to show long sections of the journey taken by the Ro family, a mother, father, two children and a grandmother who crossed into China on their own. As Pastor Kim assists them in getting beyond that, we see them in cars, in safe houses and in the jungle. “The footage in this film was shot by our subjects, by operatives in the underground network, and by the filmmakers,” says an opening title card. And part of what is shown in “Beyond Utopia” is the Ros’ acclimation to living outside of North Korea. The grandmother, who says they were taught that Americans were evil, begins to think she was misled. “As I look at you and see how kind and nice you are,” she says, presumably referring to an offscreen Gavin, “this makes me think perhaps my government has lied to me somehow.”

Lee, on the other hand, is reduced to suspenseful communications by phone. Her efforts to extract her son have a less heartening outcome. Neither she nor the filmmakers can breach that wall.

‘Youth (Spring)’ (2023)

Wang Bing’s sprawling, three-and-a-half hour documentary follows the lives of Chinese garment workers in their late teens or early 20s who have sought work in Zhili, a district of Huzhou province. According to the closing credits, there are more than 18,000 textile workshops there, and part of Wang’s interest is in how thoroughly the workers’ lives have been subsumed by industry. They live in dormitories. They date one another (or seek to, anyway). Housing and food are, as managers see it, part of the pay package, although at one point workers stage a protest to demand better wages, only to have their boss demur that he’s too busy to help them.

Privacy is minimal. We meet a young couple, Hu Zuguo and Li Shengnan, who have to decide how to handle a pregnancy — and the decision, in this context, is not theirs alone. (Management and parents get involved.) Repetition has long been part of Wang’s formal strategy; his other documentaries include “Bitter Money,” also about the textile boom in Huzhou, and “’Til Madness Do Us Part,” set almost entirely within the confines of a mental institution. The shops are difficult to tell apart, although title cards give their addresses. Several are on a street called Happiness Road.

But while the interchangeability of the locations can grow wearisome, that is part of the point. What is it like to live with little sunlight, on trash-strewn blocks, with the irritating buzz of sewing machines continually in your ears? Even with the epic running time, Wang isn’t done. He is said to be working on two follow-up films.