Aleksandr Mokin had lost the will to live.

Convicted of selling drugs and ostracized by his family, he endured abuse from guards and frequent spells in solitary confinement at a high-security Russian prison. He told a friend he felt alone and racked with guilt.

Then, in the summer of 2022, Mr. Mokin and other inmates in Penal Colony No. 6 in the Chelyabinsk region started hearing rumors. One of Russia’s most powerful men was reportedly touring jails and offering pardons for prisoners who survived six months of fighting in Ukraine.

And by October of last year, there he was, Yevgeny V. Prigozhin, standing before them in his military fatigues, himself an ex-con who now ran a private military company, Wagner. He offered freedom and money, even as he warned that the price for many would be death. Mr. Mokin and 196 other inmates enlisted the same day.

“I really wish to be there, knowing that this is likely to be a journey without return,” Mr. Mokin, then 35 and serving an 11-year sentence, told a friend in a text message that was viewed by The New York Times.

Two months later, Mr. Mokin was dead. A social media post showing his grave is the only known public tribute to his short life.

As the war in Ukraine grinds to a stalemate, Mr. Mokin’s ultimate legacy may be his small role in a much bigger, globally significant enterprise: He was one of tens of thousands of convicts powering the Kremlin’s war machine. Even now, with Mr. Prigozhin dead and Wagner disbanded, Russian inmates are still enlisting in what has become the largest military prison recruitment program since World War II.

In Ukraine, these former inmates have been used mostly as cannon fodder. But they have bolstered the ranks of Russia’s forces, helping President Vladimir V. Putin postpone a new round of mobilization, which would be an unpopular measure domestically. And since many of the inmates come from poor families and rural areas, it has helped Mr. Putin to maintain the veneer of normalcy among well-off Russians in major cities.

“When civilians are mobilized, they are ripped from their families, their jobs,” Aleksandr, one of the surviving recruits from the prison, known as IK6, said in an interview. “As for us, we’ve got nothing to lose.”

Some of the inmates’ reasons for choosing the war were obvious. Many said they were driven by patriotism, a desire to escape prison or a craving for action after years of confinement.

Yet interviews with the fighters and their relatives also revealed a deeper longing for redemption, a powerful emotional force in a country that has long wrestled with the meaning of guilt and sacrifice. For men stuck in the savage, dehumanizing conditions of Russian prisons, the war offered a chance to regain their sense of self-worth, even if it meant potentially taking other lives.

Enlisting has allowed inmates to provide income for families they had burdened for years — and to regain respect in a society that stigmatizes criminal records and honors military service.

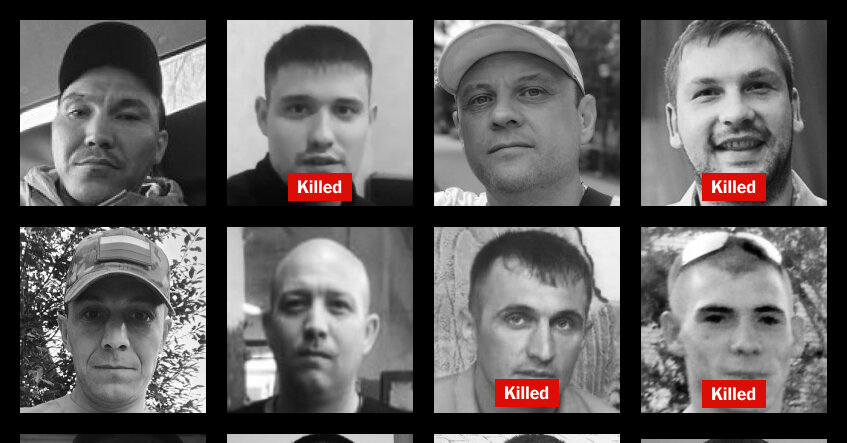

The Times obtained the names and details of the 197 initial IK6 recruits, and was able to confirm the fates of 172 of them through 2023. Times reporters interviewed 16 of them, spoke with the families and friends of others, and reviewed social media, court records and a database of war casualties compiled by an independent news outlet, Mediazona.

Together, they form the most comprehensive portrait yet of the convicts who played an outsize role in Russia’s invasion.

The harshest finding was the one Mr. Prigozhin warned of: death. At least one in four recruits who left jail with Mr. Mokin in October 2022 was killed. Most who lived appear to have suffered serious injuries, according to interviews with survivors and relatives.

Russia’s prison service and defense ministry did not respond to questions for this article.

The data shows that the recruits averaged 33 years of age and came mostly from small towns and villages. Their most common crime was selling drugs. They had, on average, five more years left on their sentences in abusive prison conditions, providing an incentive to enlist.

Some men, however, signed up with as little as three months left behind bars, suggesting other motivations than freedom.

Nikolai, a construction worker who was convicted along with his wife for selling drugs, said he joined Wagner out of patriotism. Money also helped. Even if he died, he said, the compensation Wagner promised his family — about $50,000 — would solve their housing problems. “This is wonderful, I thought.”

Even death would have meaning, if he were killed in battle. “I didn’t want to be such a bad person in the eyes of the children in our village,” he said. “I would be remembered not as a convict, but as a man who died in a war.”

‘Human Conveyor’

In some ways, Mr. Putin’s war has turned the country’s entire criminal justice system into a military recruitment tool, experts say. Russia’s extremely high conviction rates — 99.6 percent — its long prison terms, and inhumane conditions inside jails create strong incentives to risk death to obtain freedom.

Wagner said that about 50,000 inmates served in their ranks in Ukraine, and that one in five of them died. Mr. Prigozhin himself died in a plane crash in August, in what Western intelligence agencies have called an assassination, after a failed mutiny against Russia’s military command.

The Russian Army took over Wagner’s prison recruitment program in February, not only maintaining operations but expanding them.

This year, for example, the armed forces began recruiting from pretrial detention centers and immigration detention facilities, according to three Russian prison rights groups. The military has also stepped up efforts to entice Wagner’s inmate veterans back into the war.

Yana Gelmel, an exiled Russian prison rights activist who provided documents, called the system a “human conveyor” for the war effort.

“It suits the state to continue taking these men, because they don’t exist in the eyes of society,” she said.

Located outside the industrial city of Chelyabinsk in the Ural Mountains, IK6 is a sprawling walled complex of barracks and workshops. It primarily holds inmates who have been convicted on first-time offenses considered “grave” under Russian law. The range of crimes is wide: from violent murders to drug sales and robberies.

“Mostly, it was people who have slipped for the first time, but have slipped pretty hard,” said Yevgeny, an inmate who lost the use of his arm in Ukraine. “Those who have killed while drunk, young drug dealers.” Like other former prisoners, he asked to be identified by only his first name to avoid retribution.

Some recruits had sold illegal substances to bolster meager wages, a review of prison sentences and interviews show. One recruit got six years for growing marijuana and trying to sell 40 grams.

But one of three recruits was serving time for murder. This rate is more than 30 times higher than the overall percentage of murder convicts in the Russian prison system, underscoring the attraction of military service to men with long sentences.

One recruit beat his drinking companion to death with a bat, then set fire to the apartment with the victim in it. Another murdered two men with an ax following a drinking session.

Among the convicted murderers who enlisted is a veteran who asked to be identified by his military call sign, Volk, meaning Wolf.

He said his mother died when he was 6 and that he grew up in foster homes and orphanages. He was imprisoned at 20, after he and another man beat two people to death while drinking, court records show. He was eager to seize Mr. Prigozhin’s offer.

“I got tired of imprisonment, realized that this is not my place,” Volk said after returning from Ukraine. “I understood, took responsibility for what I have done.”

He said he now works as a welder and studies management.

The Prison

Mr. Mokin, the convicted drug seller, had struggled to adjust to life in a prison system that has long been plagued by corruption and abuse.

He told a friend he was constantly bullied by the guards, who punished him with solitary confinement for the smallest infractions. He lacked money to buy basic necessities like toothpaste and underwear, or enjoy small luxuries like cigarettes.

Above all, he said, he was haunted by the shame of relapsing into addiction and the guilt he felt over the death by suicide of a young woman he felt close to.

“I can’t wait till they finally get to us,” he wrote his friend, referring to Wagner recruiters.

His experience appears typical of inmates who struggle to fit into the brutal caste system of many Russian jails. Enforced by underworld leaders known as bratva, the system ostracizes and humiliates inmates deemed to have violated complex social rules that govern Russian criminal life.

Inmates in the bottom rungs are forced to act as servants, carry out demeaning tasks such as cleaning toilets, and can be subjected to sexual abuse. Drug dealers like Mr. Mokin are traditionally assigned low social status.

“All you need to make sure that people keep enlisting is to create bad conditions” in prison, said Anna Karetnikova, a former senior prison official in the Moscow region, who left Russia in protest of the war. “This is not patriotism. It’s survival.”

Reducing the abuse requires paying guards and their surrogates among the inmates, in a system where the authorities relentlessly pursue financial gain, said Nikolai Shchur, a former prison ombudsman for the Chelyabinsk region who has studied the facility extensively.

Virtually any good or service at the prison is available for a price: a family visit, a positive parole letter, drugs, the use of a washing machine. The money is usually transferred by families directly into the accounts of guards or their middlemen.

During the day, about half of the inmates produce goods in a textile or scrap metal shop for about $4 worth of monthly wages. At night, inmates are enticed to participate in marathon card games and incur debts, with the payoffs eventually trickling to overseers.

Until a decade ago, IK6 authorities collected money through violence, according to Mr. Shchur and four former inmates who served sentences there at the time.

They said guards subjected an inmate on arrival to systematic torture called a “break-in” period. Methods included brutal beatings and tying a car alarm to each of the inmate’s ears, according to an official report compiled by Mr. Shchur and confirmed by the former inmates.

The violence eventually backfired. In 2012, the inmates staged one of the largest prison mutinies in modern Russian history, a peaceful rooftop sit-in that was violently repressed by the police days later.

An ensuing scandal led to the appointment of new prison officials, who outsourced the jail’s management to the underworld leaders in return for a share of the money being extorted, according to Mr. Shchur and the former inmates.

Today, the bratva enforce obedience primarily by controlling inmates’ social status. Yet, under their rule, inmates remain dependent on the financial support of family, a burden that appears to have motivated some to enlist.

“He said that he was to blame for winding up in prison, for abandoning his family,” said the former wife of a deceased recruit, Andrei Vorobei. “He didn’t care where he died, in Ukraine or in IK6.”

A Costly Second Chance

In late April, a chartered Russian transport plane carrying about 140 former IK6 inmates landed at a military airfield outside Chelyabinsk, according to interviews and social media posts. It was the last day of their six-month contract, and they had survived.

“At first, it was difficult to comprehend that I got so lucky that I had returned,” said Nikolai, the former construction worker. “It is a feeling of madness bordering on joy.”

Most of the interviewed survivors claimed they have found respect after years of shame. One fighter, Sergei, said that on returning to his village, he changed into new fatigues, pinned on the six medals he had received, and knocked on his family’s door, where his crying mother and flabbergasted father greeted him.

“Their view of me has changed, because now everyone in the village respects them,” he said. “Their son brought back medals from the war.”

Another recruit, Aleksandr, spoke with pride about reconnecting with his estranged daughter. “She was telling everyone at school, ‘papa is at war, papa is at war,’” he said.

A few of the survivors have found factory work, and are trying to move on from prison and war. They said they are grateful to Wagner for honoring the contract terms, and to Mr. Putin for issuing pardons.

“Uncle Vova has pardoned me, forgave me and my brothers,” said a veteran, Andrei, who now works at a textile plant, using an informal version of Mr. Putin’s first name. “He gave us a second chance.”

None of those interviewed questioned the Kremlin’s decision to invade, or its rationale for war. Nor did they reflect on the atrocities and devastation Russian forces have inflicted across Ukraine in almost two years of fighting, including the deaths of thousands of civilians.

Since returning home last spring, some of the former inmates have slipped back into crime, reflecting the difficulties faced by Russians with criminal records. Of the 120 confirmed surviving IK6 recruits, nine have been charged with driving drunk, drug offenses or fraud, court records show.

Other survivors have struggled to find meaning in the decision they made, or to deal with the trauma of war.

Most of those interviewed declined to discuss details of their military service, but they have described the general brutality of the fighting. None explicitly denied Wagner’s draconian disciplinary measures, which reportedly involved the execution of fighters accused of cowardice or insubordination.

Nikolai, the former construction worker, said his initial patriotism soon clashed with what he described as incompetence and corruption among senior military officials, which increased casualties. “Our guys are out there fighting,” he said, “and these political figures are waving their little flags and moving figurines on the maps.”

Whether they survived or not, soldiers said, depended on what unit they were in, who the commanders were, and whether they respected human life.

For Sergei, the medals that reconnected him to his parents have come at a psychological price.

“There’s no sleep. Only alcohol helps,” he said. “You must understand: We walked on intestines,” he added, referring to the shredded bodies on the battlefield.

Those with severe injuries described a bleak experience. An inmate named Dmitri, who lost the use of his legs, recounted how, during a commercial flight home from a military hospital, passengers who purchased priority seating refused to make space for his wheelchair.

“My mother told them that I’m coming back from the special military operation,” he said. “They couldn’t care less.”

He has rarely left home since returning, because his mother is unable to lower his wheelchair to the street.

Yevgeny, a veteran with an injured arm, recounted his typical day in a text message: “I got up. I took my pills, put on my prothesis, put on the compression sock. I prepared breakfast, ate. Took more pills,” he said. “That’s it. Two hours had passed.”

“We were told that the Motherland is in danger, we went to defend it,” he said. “But afterward, no one cares what happens to us.”

Christiaan Triebert contributed research.